The Reverse Turing Test

Computer preparation has made top players play more like computers. This makes it harder to spot if someone is cheating.

The chess world is currently rocked by a cheating scandal. It was sparked when Magnus Carlsen, the world champion and No.1 player, lost to Hans Niemann, a 19 year old American upstart who has rapidly risen towards the top of the chess world. Carlsen initially resigned from the event (Sinquefield Cup) with the following cryptic tweet.

Later Magnus confirmed that he thought Niemann was cheating in his match. Niemann admitted to using computer assistance in some online games previously but denies cheating in this match over the board. If Niemann had been using a computer to assist him over the board, he would have had to sneak a computer past security checks. Speculators (including Elon Musk) have made some fruity allegations about how he might have done this and Chess.com have provided a detailed report of Niemann’s previous cheating online.

Effective cheating at top-level chess has been made much easier by computers. As recently as 30 years ago, it would be difficult to cheat at a top level chess event. No-one knew more about chess, than the top grandmasters. Now, each of our phones is capable of outplaying the world’s best. I do not have enough information about the Niemann scandal to make a judgement on whether he was cheating, but the case does raise the question of how we can tell computer and human chess players apart.

I explored this question by downloading the moves from each Chess World Championship (as well as the Candidates (qualifying) tournaments since 1896. I then analysed a sample of matches from each event using Stockfish, one of the top computer chess engines. This allowed me to compare the moves made by the top Grandmasters, with the moves that the computer would recommend. I only include moves after each player’s 5th move as the computer does not evaluate moves it takes as standard openings.

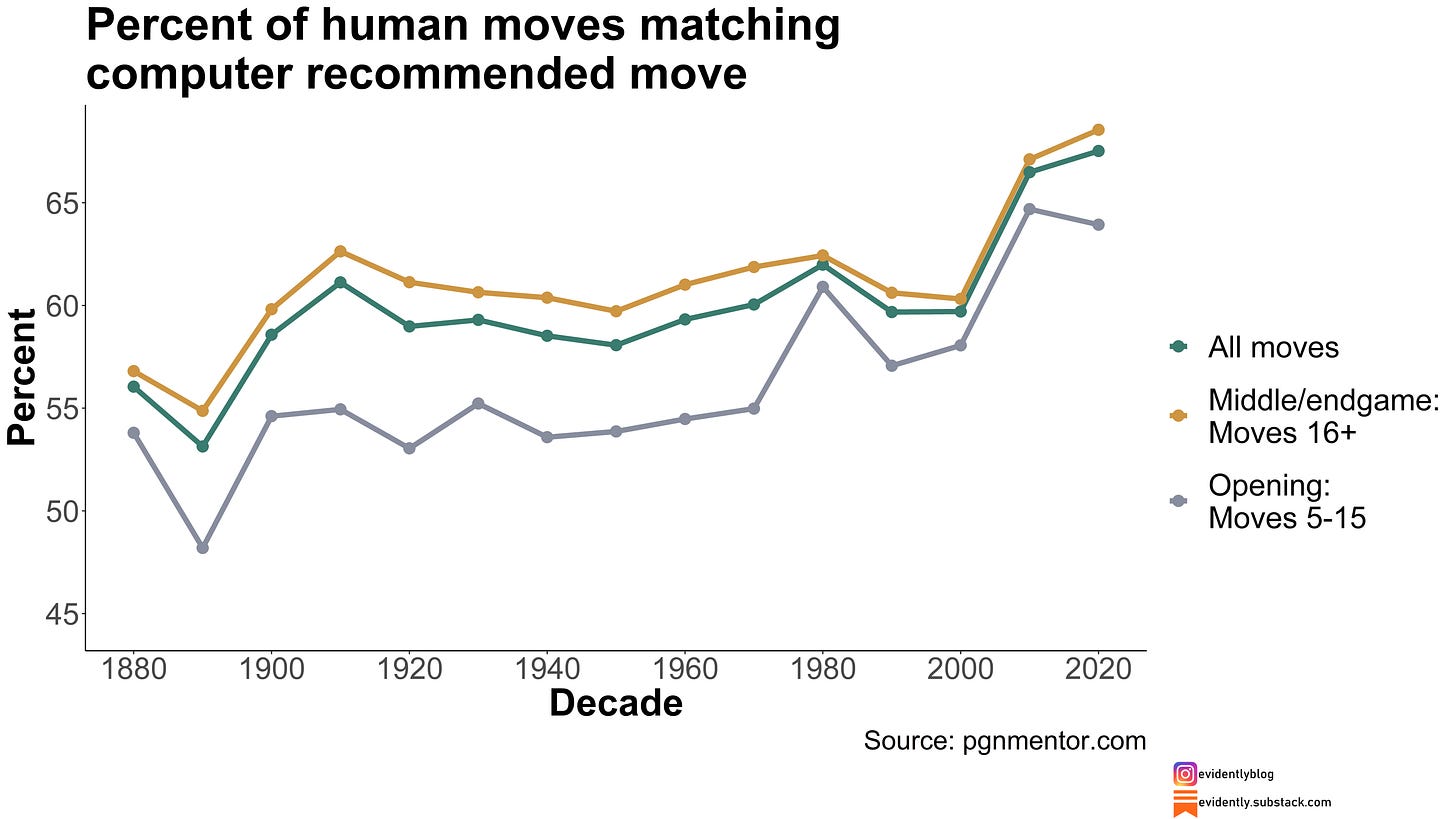

Two things stand out from this analysis. First, humans are not that close to computers. According to my analysis, between the 1910s and 2000s the average percent of moves matching the recommended computer move hovered around 60 percent, as shown in the graph above. That doesn’t mean top players are playing bad moves. Often top players make good practical moves, whereas a computer can always calculate many moves ahead and play the optimal move.

Second, in the last two decades the top chess players have become more like computers. In the World Championship and Candidates tournaments in the 2010s and 2020s the average player is matching computer moves more than 65 percent of the time. In Game 3 of the 2021 World Championship, Carlsen and his opponent Nepomniatchi played an incredibly accurate game, where 88 percent of their moves matched (or approximately equalled) the computer recommended move in my analysis.

Increased use of computers for preparation is likely the key driver of this change. While Deep Blue beating Kasparov in 1997 signalled the beginning of the computer age, it took longer for access to computers to become widespread enough for chess engines’ recommendations to be widely used in preparation. The generation of players reaching their peak in 2010s and 2020s knew how to use computers to their advantage.

Computer preparation has made top chess players more computers like in two ways. Firstly, top players can now memorise computer recommended moves in opening sequences. Secondly, top players will have learned from computers and this may alter which moves they consider later in the game. In the graph above I split out opening moves (5-15), which are likely to be at least partially memorised, and later moves. We can see that top players have not just become more computer-like in the opening moves but also later on. This suggests that humans have actually learned from computers and are starting to play more like them. This makes the task of identifying cheaters much harder. If legitimate players are learning to play more like computers, it becomes more difficult to tell a legitimate player apart from someone using a computer.

Next week I’ll write a follow up blog on how human and computer chess players differ in playing style.

(Technical caveat: I ran Stockfish with a stoptime of 1 second for my analysis, which leads to fairly low depth calculations: approximately 15. However, this paper conducted a similar exercise using a much deeper search in Stockfish and found similar percentage of correct moves.)