Better luck next time?

Most Olympic Athletes only make one games, but repeat Olympians are becoming more common

Disappointment is never far away in the Olympic Village. While some athletes achieve life-changing success, 83% of athletes came back from Rio de Janeiro in 2016 without a medal. This year, Covid-19 has caused a new kind of disappointment. 39 athletes have had to drop out of the games due to a positive Covid test or close contact with someone with a positive contact test. After 5 years of dedicated training, they have not even been able to compete.

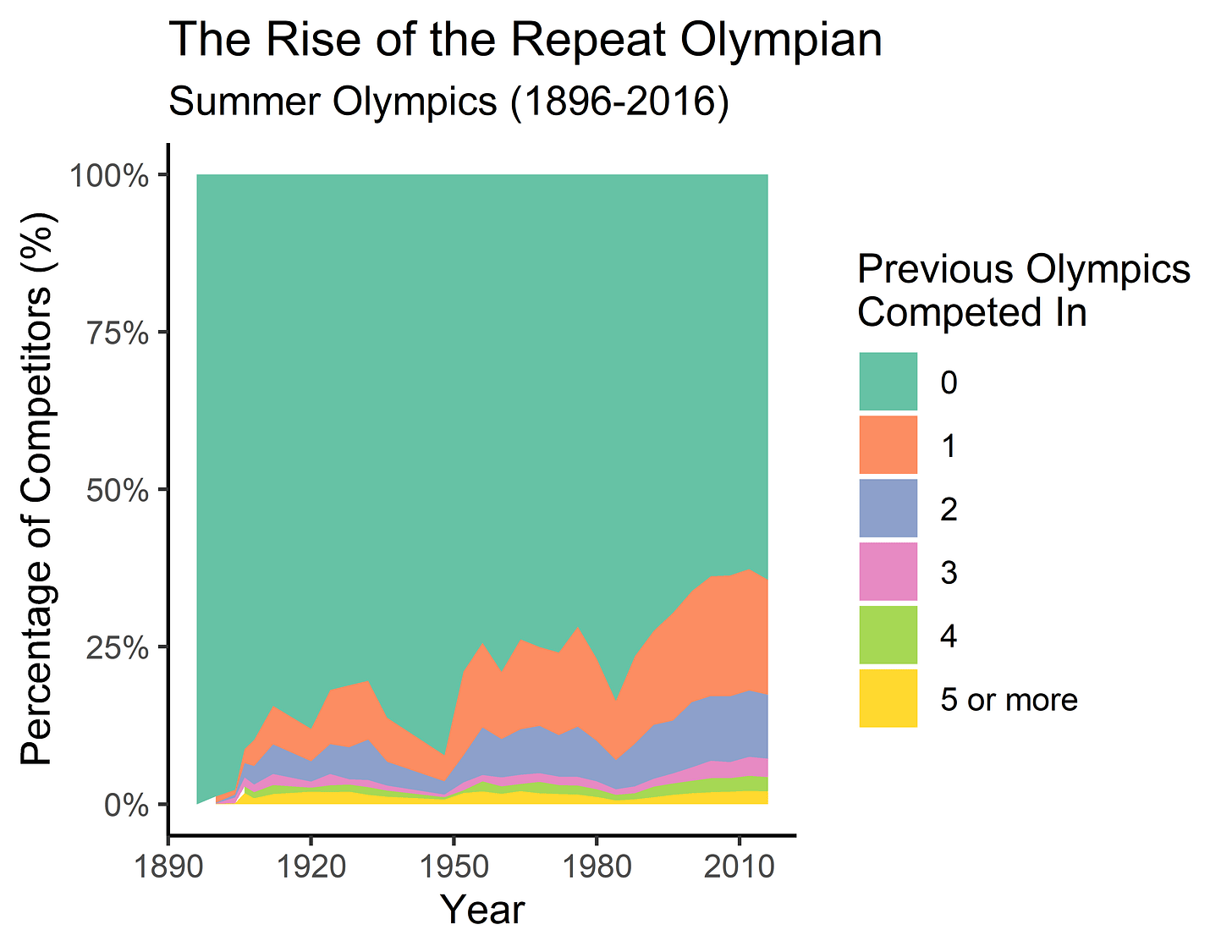

After disappointment, athletes tend to look to the future. Many athletes will already be thinking about Paris 2024. But how likely is it for athletes to come back and compete again? Data from Sports-Reference suggests that most Olympians make only one games. Of the 182,000 competitors between 1896 and 2016, 27% of athletes appeared more than once.

Competing in multiple games is becoming more frequent though. 37% of competitors in Rio de Janeiro in 2016 had competed in a previous game, while in 1920 only 13% of competitors had. The percentage of repeat competitors has gradually increased since the 1920s, except for two anomalies. The percentage of repeat competitors was low in 1948, as World War 2 caused a 12-year gap between Olympics. From 1976 to 1984 a significant number of competing countries boycotted the events, which meant a smaller percentage of repeat athletes.

What could be driving the long run trend? One factor could be the composition of events within the games. Repeat competitors are much more likely in some sports than others. In 2016, only 25% of boxers had competed before, but 53% of table tennis players had competed before. However, the trend holds for long-running sports. Amongst sports that have been in each Olympics since 1920, the number of repeat competitors has grown from 12% to 37% in 2016.

A more important driver is the professionalisation of the Olympics. Baron Pierre de Coubertin designed the modern Olympic games to be only for amateurs. No-one who had ever been paid to compete could enter. Over time this restriction came under increasing pressure. Athletes in the USSR, for instance, were provided with comfortable jobs and fully paid coaches. Sports brands started to pay athletes to wear their clothes. By 1986, the Internal Olympic Committee ended the formal ban on professionals. Better pay and support for athletes means that athletes can maintain top level competition for longer.

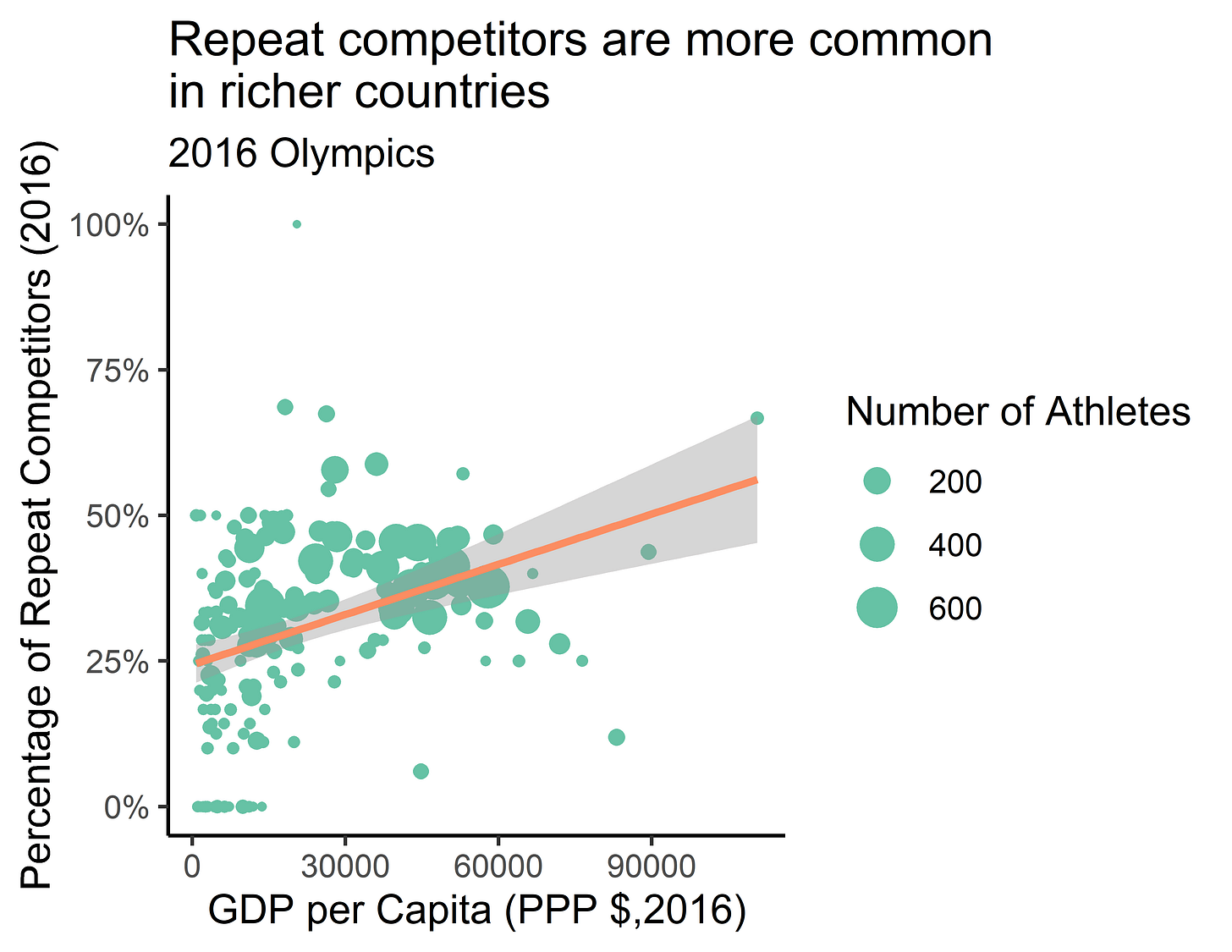

Some countries provide better support for their athletes than others though. In most cases, national sport governing bodies provide athletes with salaries, coaching and training infrastructure. Richer countries are likely to provide more support. Athletes from countries with higher GDP per capita are more likely to compete at multiple Olympics, after controlling for what event they compete in. With only 3 years until the next Olympics in Paris, many athletes in Tokyo will hope they can join the growing group of repeat Olympians.